Introducing A Matrix for Fiction

I’m going to start by breaking a few rules for literary criticism. We often attempt to use literature to analyze culture by looking solely at the content of a work, and its context in history - that’s all fine and good, but I do think sometimes our ability to view the shifts in contemporary culture becomes warped by the limits we place on ourselves. When we are discussing literature from past eras, it works - but when we’re talking about the writing of today, especially in this End-of-History boring dystopia, there are two different factors I’m interested in: the aesthetic appeal of a work of fiction, and the intended effect of a work of fiction. As can be seen, these are categories by which fiction can be separated and analyzed - and they are largely tied to market forces. Rather than attempting to analyze what an author is trying to say and what made them say that, we can see what experience authors are trying to offer their readers, and through what aesthetic means. In that matrix, we gain an entirely new insight into the relationship these contemporary artists have formed with contemporary reality.

Let’s first consider two different approaches to the aesthetic appeal of fiction, which we will split into two categories. To begin with, there is Realist Fiction: stories that take place in the real world, and whose conflict deals with real material - a world is not at danger, but the thoughts and experiences of the protagonist are open for the audience to inspect. Catherine Gallagher, a critic well-known in the field of the history of realism, wrote that the appeal of realism is how closely the writer’s work is to recreating real life. The aesthetic is simulation - the reader may feel fully engrossed due to the tools used by the writer to recreate recognizable aspects of experience. This can range from density of detail to techniques to put the reader in the protagonist’s head, such as free indirect discourse.

The other category would be that of Worldbuilding Fiction. Here the appeal is quite the opposite to that of Gallagher’s theory - the further the writing distances itself from the real world, the more appealing it is. This is fiction that utilizes techniques such as supernatural settings, fantastical worlds, new species, and so on. This fiction transports the reader away, and entertains them through an engagement of their imagination.

When we then discuss the matrix of intended effect, we are then talking about the reason behind the appeal of the aesthetics. Different readers come to books for different reasons - at the end of the day, reading is an investment of time and effort. It is not so simple as the malaise of television - there is active engagement, though for varying reasons. Authors are incredibly aware of these effects - they are readers themselves, and often write to appeal to what readers are trying to find in a book.

The most common and understood appeal of fiction is Escapism - we can consider the literature in this category as Escapist Fiction. Escapism is something that is present in all creative modes of storytelling. Just as consumers go to Marvel movies and science fiction video games as an escape from the everyday, they also may go to different forms of fiction. The goal of this type of writing is to offer a route by which readers can be so absorbed that the worries of their everyday life leave them. Rather than worrying about the mortgage payments or the stress of work life, they can be lost in a book, fully engaged, so much so that time disappears from them. We have all experienced this - even if it is not what we have gone to a book for, we have experienced the feeling of becoming lost in a work of fiction, completely absorbed, to the point of losing track of space and time. It acts as a window through which a reader can stare out and daydream, lost to time.

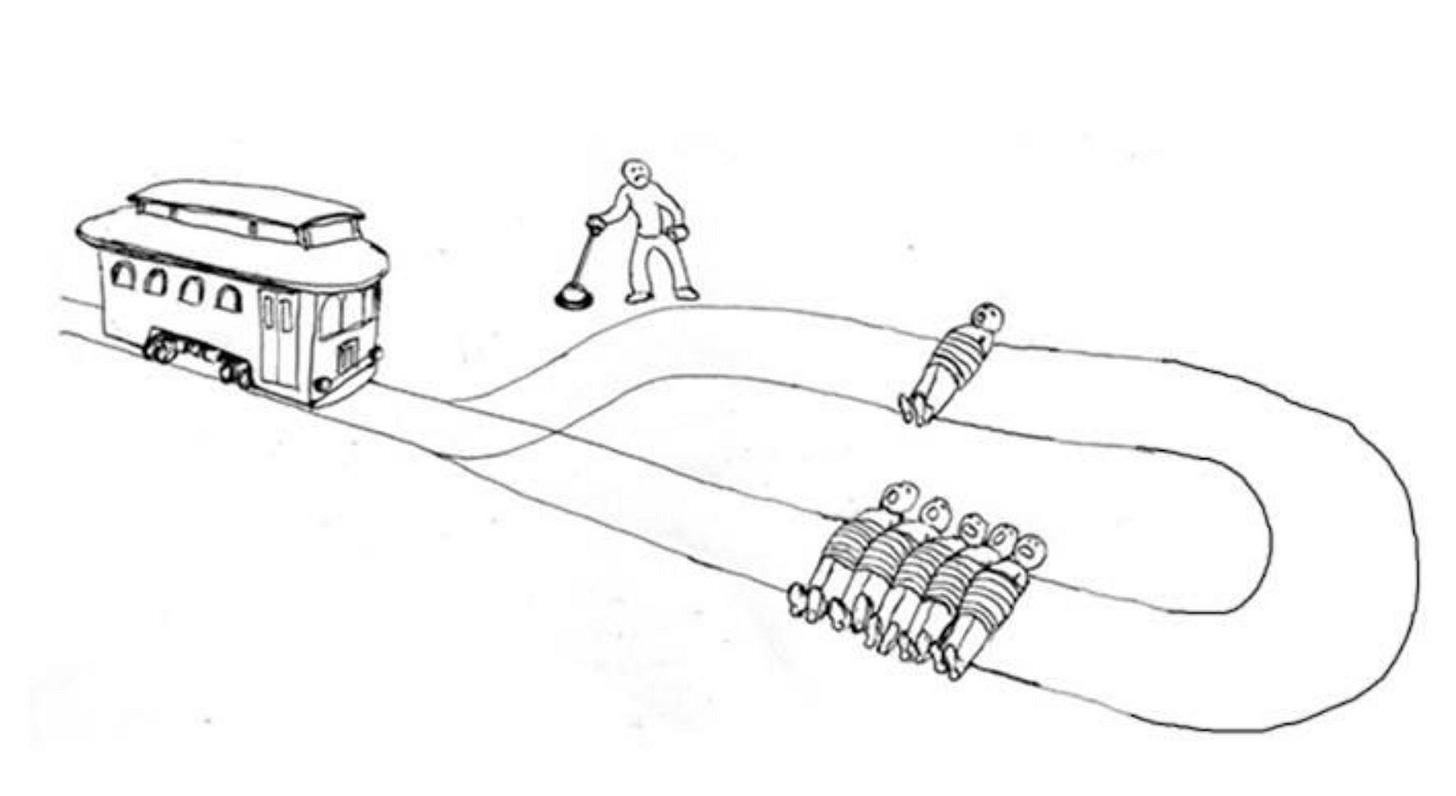

On the other end would be fiction that I would dub Provocative Fiction - we can view this as the foil to Escapist Fiction. Provocative Fiction is not simply of this world. It is direct, specific, and message-based. Though a reader can be engaged thoroughly by this type of fiction, it does not allow escape from the world - rather, it forces the reader to look deeply at it, with a questioning eye. Provocative Fiction is interested in inspiring change. There is a concept often claimed to be from Chekhov that the job of an artist is questions, not answers. Provocative Fiction’s goal is the implanting of questions into the minds of readers. In the concept of windows, it rejects the view outside and instead offers a mirror through which a reader is forced to turn back on themselves, back on their world, back on the status quo.

With these four axes of fiction built, we can begin to see where normally the aesthetic appeals and the intended effects align. Naturally, the technical elements of Worldbuilding Fiction align best with the effects of Escapist Fiction. Escapist Fiction often relies on worlds outside of ours: exploration of space, fantastical worlds, etc - basically, storytelling that relies on worldbuilding. It is far easier to engage a reader into total engrossed escape when engaging their imagination. For an ironic example, consider a series like Hunger Games. Though set in a dystopian world, unless we actively analyze it, it is more an engrossing piece of fiction than a morally-charged commentary. Our interests, as readers, is exploring this new world, imagining the various elements, and being enraptured by the described action scenes.

On the other side of this matrix, Realist Fiction often plays the role of Provocative Fiction. This is, historically, the form often through which moralizing takes place in fiction. Rather than forcing the reader to utilize their imagination, the reader’s focus is turned towards relatability. The physical details of the story are recognizable. The physical similarities lead the reader to draw lines of connection to the reader’s own life. How do they relate to the various characters? Have they ever found themselves in similar situations? Considering the vast history of realist fiction, this all makes sense. Daniel Defoe’s novel, Moll Flanders, a seminal work in realism, utilizes even a preface that insists it is actually a journal that Defoe found on the ground and edited. When later pressed on the topic, Defoe released a second preface that admitted he only did so because he believed his readers would not take the novel’s moral instruction seriously if they did not believe it to be true.

The thing is, it wouldn’t be worth writing an essay about if this was solely the point - to establish terms and categories that reflect well-known facts. It’s common knowledge that, in modernity, humans have turned to depictions of reality to discover the flaws and possibilities within our status quo and that, similarly, humans have used their ability to imagine other worlds and realities and societies to entertain fantasies, to distract from the status quo, to find relief in the childhood act of imagination. I could stop someone on the street and they’d, in at least general terms, be able to repeat this concept.

However, a noticeable shift in the past decade makes these genres worth noting. In the short history of America, the 2010s have contained radical changes in rapid succession. The great failure of the Iraq War. The Recession and the bailout only for corporations. The rise of social media culture, introducing entirely new ways not only of communicating but recognizing one’s self. And, in the world of contemporary fiction, with an ever-shrinking economy, a major shift has taken place - Realist Fiction and Worldbuilding Fiction have switched places - their technical details no longer fulfill their normal intended effects. And the ever changing world has come to demand new approaches.

The Switch: Introducing Autofiction and Metafamiliar Fiction

When the world changes, fiction reflects the change. Usefully, however, the categories we struck out at the beginning are objective - their alignment is what is fluid. So - what has stayed the same? Well, the intentional genres still exist. Writers aim to create works of Escapist Fiction that can take a reader away from their personal worries, and works of Provocative Fiction that prod the reader with questions regarding the status quo. The reign of screens does not mean that the window and mirror no longer have value to the everyday consumer of fiction.

However, as stated prior, what has changed is a switch: on one side, the tools of Realist Fiction have become more useful to the effect of Escapism. You see, Realist Fiction, as it entered the 2000s, faced an issue as to what future technical achievements it could find. The literary improvements it had pursued throughout literary history seemed to have all been discovered, and its market surface appeal was beginning to fall in the face of reality television and social media. These two forces influenced contemporary realist fiction. The solution to a falling market of readers is to succumb to the times. What emerged, I would argue, is what could be considered the genre of Autofiction.

Autofiction’s etymology is the merging of autobiography and fiction. The book is written as if the author is telling their own life story - often using a first-person perspective, the protagonist usually also shares the same name as the author. Furthermore, though fictitious, the aspects of the novel - setting, events, characters - often are ripped straight from the author’s life. If a reader should wander over to Google to investigate the author, they will find enough info to convince themselves that this book is more fact than fiction, making it appealing on the same level as eavesdropping. The appeal of Autofiction is similar to that of gossip - to know about the author through the character.

At first glance, one could think this technique further emphasizes the relatability of these novels. However, things are never so simple. The tone, though first-person and always close to limited to the narrator, distances the reader from the protagonist through deprecation. These novels are comic - their point is to make the main character seem ridiculous to the reader. The protagonist is awkward, lazy, and in lightly absurd situations. Lerner’s novel, 10:04, begins with the protagonist eating octopus and obsessing over his friend’s recent request for him to inseminate her, but not through sex. The set-up is immediately understood - this guy is a neurotic weirdo for us to laugh at. And this exists in all of Lerner’s work: the stories of a pathetic man who exists for the sake of ridicule. All of this is in the wink to the audience that this character is the author actually.

This mix of comedy and “auto” serves to distance the reader from the protagonist. And a useful model for this is reality television. Reality television is, as we all know, rarely ever real - however, the act of pretending it is leads to a far more enjoyable program. It is much more fun to smack our heads at the stupid decisions, mock the ticks and habits, and laugh at the major failures of real people. Autofiction engages the reader in a similar way. Rather than some figure through which a reader can understand themselves, the protagonist is a fugue to laugh at the author through. And, with that, they become Other, and the story is not relatable. It is only entertaining. Autofiction becomes escapist through this distancing and, in this sense, a relief for readers. In the realm of mirrors and windows, Autofiction takes on the window in a new take - rather than a daydreaming gaze, it offers the appeal of a peeping tom’s window - to look and spy and judge, devouring the surface level personal details to mock and escape from the tree one balances on.

However, on the other side, the tools of Worldbuilding Fiction found a new usage. For the sake of our discussion, I will utilize the phrase Metafamiliar Fiction. Let’s pick it apart to explain my choice in designing this term.

The metaphysical poets of the Renaissance gained the title through the wide distances between the nodes of their metaphors. Consider John Donne, who compares a flea drinking blood to sex. No one would consider the two similar, but a metaphysical poet is able to use the distance to their advantage. This is where the “meta” in metafamiliar fiction comes into play. For the “familiar” aspect, a useful term to understand is the concept of “defamiliarization.” Sourced from the essay “Art as Technique '' by Victor Shlovsky, defamiliarization was initially an observation on a technique of description. From Shlovksy, defamiliarization can then be understood as making something normally common into something strange - an object that we would not pay attention to is now suddenly surreal and out of place.

The fiction that makes up Metafamiliar Fiction is otherworldly - it, upon the start, is easily recognizable as something taking place not in our reality. In fact, the difference is so pronounced, one can be drawn to consider some of these works as science fiction or fantasy. But - upon reading a piece - the reader is forced to realize that these widely separate worlds have disconcerting parallels between them. The writer creates massive metaphors through the techniques of worldbuilding. What would normally seem completely separate from real life becomes eerily similar - different realities, often dystopian in tone, become familiar.

Consider the story “Offloading for Mrs. Schwartz” by George Saunders for example. In it, we are following the life of a man who runs an arcade for simulated memories, who discovers he can steal the memories of an old lady he’s friends with to sell them to schools. On the surface, it doesn’t seem particularly relevant. It mainly seems weird. However, in the process of reading, similarities set in. The way memories slip from Mrs. Schwartz’s mind mimics dementia. The money problems of the main character ring realistic and recognizable. The correlation between the two suddenly recalls the issues with our own senior care state in America, and suddenly a very strange funny story has made you incredibly sad for the fate of the characters. It is an almost Aristotelian catharsis. That tragic effect also ties the reader into considering their own life, their own sacrifices, and their own priorities in the face of their own financial state.

As can be seen, this form forces the reader to make a distinct comparison between their reality and the reality the work is set in. It refuses escape, but is far more complex than a mirror - the reader is thrust into the world now with an inspecting eye. It is complicated and harsh and sometimes abrasive, but it illuminates a reality arcing towards an asymptote of dystopia in a way no other form has done before. In the metaphor of the window and the mirror, we see a genre working more like a car mirror - the objects that appear are far closer than they appear. And, similar to the car mirror, Metafamiliar Fiction is not simply a route to provoke questions - it is an almost indispensable warning of imminent danger.

What Do We Make Of Change in Tiny Arenas

I’m turning cynical faster than I ever expected I could. How much have I just written only to ask myself “who gives a shit?” Past the insecurity that haunts anyone who has the arrogance to claim their words have weight, however, I’m going to say that it’s a fair point in this case. The audience of contemporary fiction is shrinking rapidly. And, the class nature of its audience has only become narrower - literary fiction was always a middle class and higher genre. But, as the class system in Western society has only further stratified, and more affordable options of entertainment and education have risen to the top, it is only a select privileged few who take the time to read the latest work deemed worth reading by the mysterious cabal of reviewers and critics. So why is it worth discussing these changes that only serve a small audience?

Well, because there are powers at play. By perhaps coincidence, the class of people who can afford to read are also the class with the most deciding power in the political arena - well educated upper middle class citizens. To that purpose, our dueling genres of contemporary fiction - Autoficiton and Metafamiliar Fiction - serve their intended purposes to different immediacies in relation to this newly powerful small audience.

Autofiction, as an escapist genre, obviously allows a relief from any political motivation on the parts of readers. The popularity of reality television and social media have changed how we look at each other. With the internet allowing every person to commodify themselves for the sake of emotional acceptance, we now struggle to see people as more than commodities whose lives are stories, not realities. Autofiction commodifies the author’s life, and implements a tone that helps the reader further view the life of an author as entertainment. However, it also trains the reader in how they look at other people - when Escapist Fiction in the past was a window into different worlds, the separation between aesthetic technique and reality allowed for a distance between how the reader acts in the real world. But consider, for a second, what Autofiction teaches us to do. It hampers our ability to view our peers and neighbors as people. Other lives are no longer relatable to us - instead, they are factories themselves, producing the gossip-worthy stories for deprecation. And when we lose our ability to relate, to put ourselves within others’ shoes, we lose our ability to understand the plight of subaltern classes. Instead, working class struggles become consumable stories - either for the sake of mocking or for watered down entertainment. Real life is no longer effective - it is solely to be consumed.

However dire that may seem, Metafamiliar Fiction is both hopeful and incredibly terrifying in its own right. Exaggeration, as a necessity in moral signaling, has always existed. Exaggerations are a useful reference point - yet, Metafamiliar Fiction rings more akin to a desperate warning than a whimsical aesthetic choice. Consider the metaphor I used earlier: objects in the mirror may seem closer than they appear. Metafamiliar Fiction resides in the place formerly occupied by realist fiction, utilizing worldbuilding techniques for the exaggerated dystopian image. These authors are begging their readers to investigate the world around them far more actively than prior. When you consider the peers of Daniel Defoe, the moral instruction was not that desperate. Small internal changes were what was necessary. With Metafamiliar Fiction, however, the moral change is external. The oppressive pressure of the status quo is barreling down on the protagonists, and their incapacitation’s cathartic effect turns the audience towards the reality we live in. Are there many differences between the exaggerated reality within a Saunders short story and our reality? Perhaps the span of a decade only separates the two - and is it a decade of inaction, of allowing the status quo to continue its downward spiral, that separates us from Saunders’ dystopian vision?

The thing is, fiction has always served a purpose of change and inaction. It serves the middle class and above, as it has always been the middle class that could afford to access this form of storytelling. That being said, the extent to which each persuasion has changed. The extremity of pushing audiences towards escapism and provocation in these two genres is far more than prior - and that is a reflection of where we stand currently in the world. The current state of the world demands two distinct extremes - a fiction that begs us to ignore it, to become lost in the surface level entertainments of the mundane and everyday, and a fiction that begs us to compare, to imagine the worst possible results to the point of hilarity, and then look back at what surrounds us to spot the difference. Writing will always reflect a contemporary state of reality - and, as we dance further towards a cliff of financial collapse, destructive class disparity, and climate crisis, the fiction that appears on bookshelves for too much money will reflect the teetering nature of that cliff.